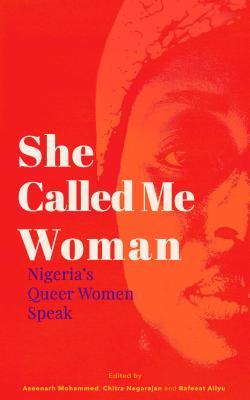

She Called Me Woman is a collection of 25 essays about the lives of queer Nigerian women. The editors of the book travelled all over the country to meet with queer women and collect stories about their childhoods, relationships, coming out processes, families and communities.

The editors themselves admit that they were surprised by what they found since the media and politicians try to paint a picture of Nigeria as a deeply homophobic, bleak place for LGBT people:

“We expected more despair and loss, but instead we found joy and resilience. [...] Indeed, the positive reactions in this book are a far cry from the dominant narrative in Nigeria that ‘everyone hates gay people’.”

There are definitely stories of prejudice, rejection, discrimination and violence. But there are also a lot of stories about supportive friends and coworkers, accepting families, allies in the educational and medical system.

In the very first essay, a trans woman recalls how her family took her to a psychiatric hospital for conversion therapy, and instead the doctors validated her gender identity and gave her family educational materials on trans issues, which lead to her brother becoming one of her biggest allies.

The women in these essays have queer friends, they attend queer events, have casual sex, monogamous partners they live with, they discuss childhood crushes and future hopes. The importance of money and financial independence is a recurring theme, as are generational differences when it comes to homophobia. A lot of the narrators feel that the generation of their grandparents are actually a lot more open minded than the middle generation of their parents who have been exposed to politicised homophobia:

Year of publication:

2018

Country of publication:

Nigeria/UK

Page count:

344

Would I recommend this book?

Yes

“My grandmother, when she watches The Ellen DeGeneres Show, will say, ‘Oh, she’s married to a woman. I like her.’ If it were my mother, I am sure it would have been another statement. I think older people, not fifties or sixties but seventies and above, are more tolerant because it was normal in the culture back then - female-female and husbands having lots of wives and stuff going on between the wives.”

They also feel that the younger generation, influenced by the internet and pop culture, is more open minded.

The editors express the regret they weren’t able to include more older interviewees (the oldest one was 42), but the book still manages to cover a lot of ground and capture both the specificity of the local context, language and politics, as well as the universality of queer stories.

The essays are based on interviews which are transcribed and edited into chapters, leading to a very conversational, earnest style. Some essays would benefit from additional edits - you can often guess the questions behind different paragraphs and the paragraphs aren't always ordered chronologically or by topic, leaving some essays feeling disjointed. It doesn't majorly detract from the reading experience though, as the casual tone of the book is quite forgiving and the life stories themselves are interesting enough to make up for any editorial hiccups.

About a third of the essays in the collection are about bisexuals, a couple about trans people, and the majority are about lesbians. Bisexuality is present even in the essays of narrators who are not themselves bi but who have bi friends and lovers, as well as observations on bisexuality. Some of them are biphobic, but there are both bisexuals and lesbians who also criticise biphobia in the community.

I expected to have to traverse some distance in order to connect with the women in this book, but actually the struggles, the joy, the fun and the inter community drama were very much familiar! Overall, a pleasure to read.